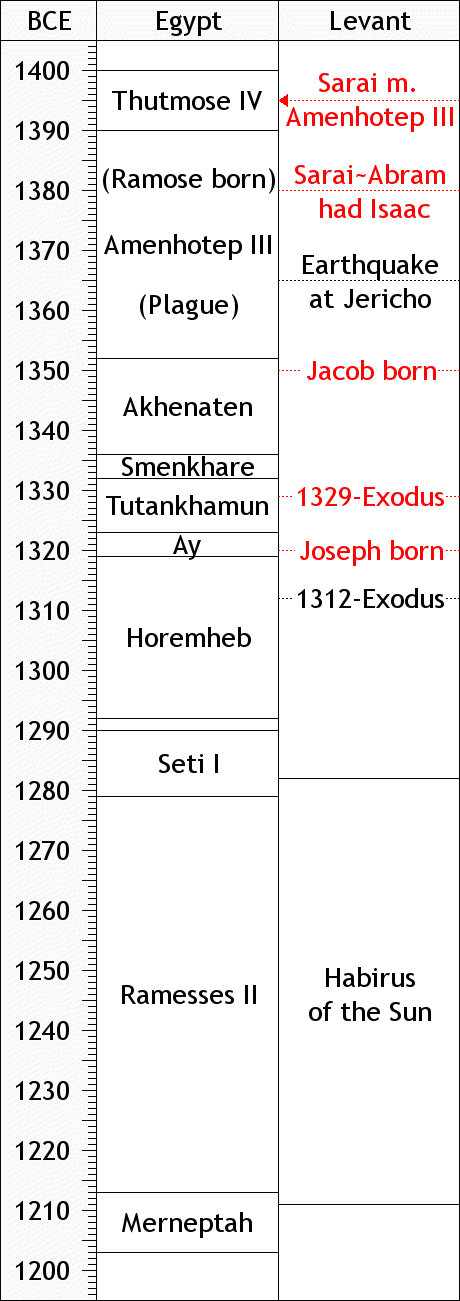

© Charles ChandlerIn the present thesis, there was a brief period in which Hebrews & Israelites were distinctly different groups, Hebrews being a mix of Egyptian Atenists & Transjordan Bedouins in Moab who moved into Canaan around , and Israelites being Jacob's descendants, already established in Canaan by that time, but from entirely different stock.1:279 Previous articles told the story of the Hebrews, beginning with the Amarna heretics, through their expulsion by Horemheb (partially in and completely in ), onward to Moab where they fell in with the Bedouins, ultimately crossing the Jordan in to build the "Land of the Habirus of the Sun" in the Judaean Mountains. Now we should consider the history of the Israelites. The Torah says that they were the descendants of Abraham, who had been granted Canaan by God,2 which they would inherit on completion of the Exodus.3So, was Abraham an historical figure? His name doesn't appear in the secular records, but that doesn't necessarily mean much. Abram and his half-sister Sarai,5 who he married, are said to have changed their names to Abraham and Sarah.6,7 The mere addition of an aspirated "H" isn't much of a change, so we should suspect that the author is telling us that they previously went by unrecognizably different names, and that these are the new names of you-know-who.8:55 "Sarah" wasn't even a name — it was a title, meaning princess, or secondary wife, so her name was definitely something different. "Abraham" might have also been a title, if it was derived from Brahmin, in which case a'Braham would have been short for The Priest. The original names would have been expunged when Merneptah bragged that he had already wiped out all of the Israelites, for fear that he would come back to finish the job. But the scribes might have left enough clues for us to determine the historical identities of the Patriarchs.As the story goes, Terah & Abraham moved from Ur on the lower Euphrates to Harran,9 the probable capital of Mitanni,10:231 at the upper end. Then there are two stories of Abraham giving up Sarah to a king,11,12 and another nearly identical story, except with Isaac giving up Rebekah.13 The first king was an unnamed pharaoh, who then rejected Sarah because of "serious diseases inflicted on the pharaoh and his household" due to her presence. The second king was Abimelek of Gerar, who is believed to be Abimilku, governor of Sur,14:104 mentioned in the Amarna letters,15:EA254 and thus a contemporary of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten. If we get the rank from the former story, and the date from the latter, Sarah and/or Rebekah were hooked up with Amenhotep III and/or Akhenaten.There are, indeed, records of Mitannian princesses marrying Egyptian pharaohs in the time of Amenhotep III & Akhenaten, and only for three generations were relations between Egypt and Mitanni so amicable.from Russell (2013):Gilukhipa (c. ) was the daughter of Shuttarna, king of Mitanni. She was married (c. ) to Amenhotep III, king of Egypt (c. ) as a secondary wife. Her elder sister or half-sister Mutemwiya was the wife of Tuthmosis IV, and mother of Amenhotep III, her own nephew. An historic scarab, issued at this time, announced the arrival of the princess, in the tenth year of his reign (c. ), and revealed that Gilukhipa was escorted by 317 women of her harem, who acted as personal ladies-in-waiting. She was accorded the regal title and had her own court at the palace of Malkarta, but left no recorded children. When her niece Tadukhipa, the daughter of her brother, King Tushratta, was also sent to marry Amenhotep (c. ), her brother wrote proudly to Amenhotep, asking him to compare the dowry he sent with his daughter, which he considered even more lavish than that which had been provided for his sister.Note the similarity between Gilukhipa's 317 servants and Abraham's 318 servants mentioned in the Torah.16,17 Of course, the 318 servants who went on campaign with Abraham were men, while Gilukhipa's 317 servants were women. Perhaps the men were the husbands of the ladies-in-waiting.8:52 Or the number 318 was a literary device, perhaps to say that Abraham & Sarah were expelled from Egypt with one more servant than they had when they arrived,18 thus identifying it as an amicable split. Regardless, we know of three generations of Mitannian princess-brides (i.e., Mutemwiya, Gilukhipa, & Tadukhipa) from Egyptian records, and in the Torah, we have two generations of Mitannian men giving away their half-sisters (Sarah & Rebekah) to Egyptian royalty, with the present detail aligning Gilukhipa with Sarah, and thus Tadukhipa with Rebekah.In the Torah, God inflicted serious diseases on the pharaoh as punishment for marrying Sarah, since unbeknownst to him she was already married to Abraham.19 There must have been more to the story. If Sarah was Gilukhipa, her pharaoh would have been Amenhotep III. There is abundant (if indirect) evidence of the outbreak of a very serious disease during his reign, in that he commissioned more statues of Resheph, the Canaanite god of the plague, than all other statues combined.20 But why would the pharaoh have maintained that the plague was Sarah's fault? The article on Jethro, Balaam, & Job explores the possibility that Abraham was indeed a priest,21:1:28 and a prophet,22 and that Amenhotep III was actually rejecting the prophesy as much as the prophet himself, thereafter insisting that the event be recorded as the expulsion of a disease. Erecting statues of a Canaanite god of the plague might have been more than just invoking the powers of the god most likely to help them — it might have been a public reminder of Amenhotep III's political agenda, that Abraham & Sarah be installed in said region and blamed for the whole thing. Then Abraham would have a tough time developing a following in Canaan, since people would avoid him like the plague, and the prophecy would be duly suppressed, in Egypt and on the frontier.Then there was another angle — in , King Tushratta of Mitanni (Shuttarna's son, and Sarah's half-brother if they had the same queen-mother) invaded Egyptian Syria.15:60/85/101 It's possible that Tushratta was too greedy in cashing in on the marital alliance, causing Amenhotep III to rescind.8:52 The story in the Torah reads as if the marriage was never even consummated, but the rejection could have been 15 years later, in , due to Tushratta's actions. If so, Amenhotep III began the plague propaganda just when he was losing territory to Tushratta. Either that was coincidence, or the events were coupled — perhaps Amenhotep III didn't care to defend his frontier against the advancing Mitannians, so instead, he hyperbolized the risk of plague in Canaan, such that the Mitannians wouldn't care to take it.A contemporary account from Ugarit tells of a "woman of Terah" and various tribes being ousted from the Negev.23:215 This is where Abraham was said to have settled before being expelled.12 If the "woman of Terah" was Sarah getting kicked out in response to Tushratta's aggression, this tells us that she and Abraham had the same father (i.e., Terah), but since they were half-siblings, they had different mothers.5 For Sarah to be a Mitannian princess, her mother had to be the wife of King Shuttarna II.As a secondary wife to Amenhotep III, Sarah would have had entitlements, perhaps including titles in Canaan, the Egyptian frontier facing her Mitannian homeland. While she was still in Egypt, her half-brother Abraham could have been made the honorary administrator of Sarah's entitlements. If so, it would have established the precedent for the Covenant, which the Israelites would later call their inheritance.24 Then, when Amenhotep III expelled Abraham & Sarah in , he would have let them retain control of Canaan, as long as they considered themselves to be Egyptian vassals — that way, if Tushratta pressed any further south, he'd have to fight his own step-brother & half-sister, and their allies still in Mitanni, along with the pharaoh, which would be too much fight for a territory infested with the plague. That the Covenant with Abraham & Sarah was a vassalage, and not just a concession, was indicated by the terms — all of the males had to get circumcised,25 which was an Egyptian custom.26,27:34 So Amenhotep III gave Canaan to Abraham & Sarah on the condition that the male heirs be permanently marked as Egyptians. This is also when the Lord gave them new names,6 which would have been a public demonstration of his power over them.Amenhotep III might have exerted a little power in private as well. Abraham & Sarah probably didn't have any children by each other, being too closely related. And the Torah doesn't say that they did — it says, "...the Lord did to Sarah as he had promised. And Sarah conceived..."28,29 This could have been the Lord Amenhotep III giving Sarah a baby in the worldly way. Of course, royalty during this period liked to stir up the gene pool, while the acknowledged father was whoever raised the children, which in Isaac's case was certainly Abraham. And the Lord said to Abraham, "through Isaac shall your offspring be named."30 So Abraham was to treat Isaac like a son, including passing his titles to the boy. The Lord further stipulated that Abraham must send away his concubine Hagar, along with their son Ishmael,31,32 such that the Covenant would pass exclusively to Isaac. This would have displeased Abraham, who would have thought that when the Lord Amenhotep III said previously, "To your offspring I will give this land,"2 it would be to Abraham's very own son,33 not to Sarah's by the pharaoh himself. With the Covenant passing to Isaac, the grant would revert back to the pharaoh's family. That might have been the motivation for the Binding of Isaac.34What was the nature of the grant to the Patriarchs? It wasn't outright ownership, since that would have made Abraham a vassal king, and there wasn't any king of Canaan — during the period in question, all of the city states had their own chiefs, who reported directly to the pharaoh. But there does seem to have been a position known as the "King of the Retjenu," which would have been something like a minister of trade. Somebody like that wouldn't necessarily have been mentioned in the Amarna letters. And such a position would be consistent with Abraham being described as a tent dweller.35 If he had been a vassal king, he would have spent a lot of time at his palace, but he didn't even have a palace. In fact, he didn't even seem to have any land, having to offer to purchase some for a place to bury Sarah when she passed, which kings don't have to do. So in what sense had he been granted everything from the Suez Canal to the Euphrates River? Perhaps he was given responsibility for the whole territory, while his duty to the pharaoh required that he travel throughout the region, making sure that the pharaoh's interests were protected.Hence the best inferences that can be drawn, all sources considered, are that:

- Terah was a nobleman (otherwise his daughter by the queen of Mitanni would not have been considered a princess fit for marriage to a pharaoh),

- Abraham was likewise a nobleman, by parentage as well as by the intermarriage of his family with Mitannian and Egyptian royalty, and who was the first administrator of the Covenant,

- Sarah was the daughter of Terah by the queen of Mitanni, and the wife of Amenhotep III, whose entitlement to Canaan became the precedent for the Covenant, and

- Isaac was the son of Amenhotep III & Sarah, who was raised as Abraham's son, and who inherited the Covenant.

With that as the general idea, now we can fill in the dates. For Sarah-Gilukhipa to be married in , she had to be at least 15 years old or so, meaning she had to have been born not much later than . Abraham was born 10 years prior,36 so he was born . This is consistent with Abraham coming 14 generations before Solomon,37 who was born .38:20 At 30 years per generation, 14 generations = 420 years, so Abraham would have been born .Isaac would have been born in , just after Sarah's expulsion from Egypt and subsequent marriage to Abraham,39 when she was 30 years old. Thus he didn't come along too soon to have been in contact with the Philistines,40 who were not present in the Levant before .8:53 Nor did he come along too soon to be younger than Ishmael, Abraham's son by Hagar. If Abraham moved to the Negev when Sarah married Amenhotep III in , and if Ishmael was born 10 years later,41 he was born in , 5 years before Isaac in .Abraham would have lived to be 75, if he died when Isaac was 35 years old.42:27:8 So Abraham died in . Sarah had already died. The story of her passing attests to the prominence of Hittites in Hebron.43 The Hittites never officially held anything that far south, so we can only guess that this would have been during the greatest southern extent of the Hittite Empire, which was during the reign of Suppiluliuma I (). If Sarah died before Abraham, but sometime after Suppiluliuma came to power, the date range would be , when she was between the ages of 60 and 65. That the passages refer to Abraham as a "mighty prince" suggests a period in which Hittites still respected Mitannian royalty, which would have been early in the reign of Suppiluliuma, when Rebekah's half-brother or uncle Mattiwaza was courting Suppiluliuma's daughter. (See Abraham, Rama, & Mattiwaza for more on that.)The Torah says that Abraham met with Melchizedek ("Lord Zedek"),44 who was the lord of Jerusalem, as well as a high priest. After the Exodus, the Deuteronomic history records the suppression of Adoni-Zedek,45,46 whose name also meant "Lord Zedek," also the lord of Jerusalem, and also a high priest. If those two were the same man, he could have met with Abraham before , then changed his name to ally himself with the Atenists sometime after , and then lost a fight with Israelites in , all in minimum of 43 years. If Abraham had been born much earlier, Lord Zedek wouldn't have lived long enough to appear in both stories.And clearly drawing on sources other than just the Torah, Talmud, & Qur'an, Hamzah wrote in the that Abraham arose in the time of Faridun, and that the Exodus occurred two reigns later.47:1:4 We don't have confident dates for Faridun or his next two successors, but Abraham () coming two reigns before the Exodus in sounds about right.Next, at 30 years per generation, Jacob would have been born in . If his mother Rebekah was Tadukhipa, the timing would be right — Tadukhipa was conveyed to Akhenaten when Amenhotep III died in , but then she disappeared from the Egyptian records, and it's possible that she was not interested in Akhenaten, marrying Isaac instead, and giving birth to Esau & Jacob shortly thereafter, in , when she was 16 years old.There is an Egyptian story thought to have been inspired by Tadukhipa,48 and which would gain meaning if we could fuse it together with the relevant biblical verses. A pharaoh and his brother were both vying for the same woman. She married the pharaoh, who banished his brother to the Valley of the Cedar (modern-day Lebanon). If Tadukhipa was Rebekah, the suitor sent to Lebanon would have been Isaac, who was the only Patriarch to never leave Canaan.49 And the pharaoh would have been Akhenaten, Isaac's half-brother by Amenhotep III. There is another possible correlation that is totally nonsensical unless the brothers were Akhenaten & Isaac — to prove his sincerity, one of the brothers cut off his genitals, which would be a misinformed gesture of romantic intent, and could instead be a reference to Akhenaten, whose masculinity has been challenged. Then there is a Hindu thread in the story — the brother banished to Lebanon died and came back to life as a bull, and then died again and came back as a tree, and then died again and came back as the son of his ex-wife. Egyptologists call this resurrection, because that's well-represented in Egyptian literature, but what is actually being described is reincarnation, which isn't Egyptian — rather, it's Indian, which could have found its way into the Egyptian legend via the Mitannians (such as Isaac), who worshiped Hindu gods.In his old age, Jacob was settled in the land of Ramesses,50 the only pharaoh named in the Torah. If that was the first pharaoh of that name (i.e., Ramesses I), the date range would have been . Archaeology has confirmed that people from Canaan were migrating to the Nile delta at that time.51:409 Being born in , Jacob would have been ~59 years old in , and thus old enough to be a grandfather by several of his children.52 He lived another 17 years,53 and therefore would have died at the age of ~76. And Joseph would have been born in , making him 28 years old in , when Seti I became pharaoh and commissioned a summer palace to be built at Avaris using Canaanite laborers, with Joseph as their supervisor.54,55Thus the last four Patriarchs are fixed in time by numerous constraints. Most notably, the alliance between Mitanni & Egypt at the beginning of the succession, and the references to Ramesses I at the end, have these Patriarchs firmly bracketed in this period.Several subsequent details in the Torah also fall in line with this chronology. The "long period" of the Israelites' stay in Egypt would have been the 66-year reign of Ramesses II () — the longest in the New Kingdom.56,57 Ramesses II is often regarded as the greatest pharaoh of the Egyptian Empire,58 and the population & wealth of the delta swelled during this period, as noted in the Torah.59 Then, in , Ramesses II was succeeded by Merneptah, who would have been the pharaoh who "knew not Joseph," and who began the oppression.60The reason for the oppression was said to be that the Israelites had become too many and too mighty for the Egyptians, and if war broke out, the Israelites might join Egypt's enemies. A war did indeed break out during Merneptah's reign — a famine brought on by the Bronze Age Collapse prompted a coalition of Libyans, Canaanites living in Egypt, Sea Peoples, and various tribes from the Judaean Mountains to attack the Nile delta for want of food. Merneptah repelled the attacks, and then campaigned in Libya & the Levant to destroy the power-base of the coalition. He then moved the capital back to Memphis, canceling the public works projects at Pi-Ramses, whereupon the Israelite laborers there would have been released from their indentured servitude. If Merneptah didn't want them following him to Memphis, he would have ordered them back to Canaan. If the resulting migration can be taken as an Exodus of sorts, then this whole chronology, from Abraham through Joseph, followed by the Exodus, seems to fall right in with the secular history. For this reason, Merneptah has been one of the favorites of modern scholars for the pharaoh of the Exodus.61:256,309,310But that begs as many questions as it answers. The parallels with secular history for Abraham through Joseph described in this article are numerous and specific. But then the biblical account of the Exodus has little in common with the war on the Sea Peoples — they were both conflicts, but that doesn't narrow things down much. This is odd given the volume of scripture devoted to the Exodus. Curiously, the details in Moses' story that don't match up with anything in Merneptah's time fall right in line with the situation late in the , when there would have been an Exodus of Atenists fleeing Horemheb. And there are enough details in the Atenist-Habiru chronology, of sufficient specificity, to make it just as convincing as the Israelite chronology described in this article.So which is it?One possibility is that both chronologies are correct, at least with regards to the details that belong to them, and once properly aligned with secular records. The Torah tells it like there was just one Exodus, but perhaps there were actually (at least) two of them: Atenists fleeing Horemheb in , and Israelites fleeing Merneptah in . These two stories would have been woven together in a later redaction. The likeliest period for such a major overhaul of the Torah would have been during the Deuteronomic Reform (i.e., during the reign of King Josiah, ), in which the conventional chronology was established.62,38 The likeliest reason for the redaction would have been political. Josiah had inherited a land of mixed ethnicity that he wanted to unify, and he saw the Book of the Law as the common denominator. But before he could unify his people under one book, first he had to unify the book. If it told of Israelites & Hebrews competing for control of Canaan, he needed a way of telling their stories such that they were not adversaries. So he built on the commonalities. Both groups had lived in Egypt, culminating in open conflict with pharaohs. Both groups had fled to Canaan, though they were still under enough pressure from Egypt that they had to keep their ethnicity hidden. 600 years later, their overall cultural experiences were more similar than different. So the official account really only needed to tell of one captivity in Egypt, and one Exodus.To make this work, first the redactors told the history of the Patriarchs in the Book of Genesis, covering Adam through Joseph, followed by the oppression described in Exodus 1. But when it came time to tell of "The" Exodus beginning in Exodus 2, they just stopped talking about Patriarchs, neglecting the details of their crushing defeat at the hands of Merneptah, and switched over to the story of the Atenists, beginning with the birth of Moses in Exodus 2:1-10. This was actually from an earlier period, but appearing in the Torah after the oppression of the Israelites under Merneptah, it reads like the continuous chronicle of one people. When it was published, the people would have seen what Josiah did, knowing the original stories. But they would have gone along with the redaction, because it preserved lots of details of both groups, and because the people did feel a common bond. And future generations raised in the tradition of the redaction would eventually forget the more ancient complexities that were neglected.For the purposes of evaluating the historicity of the Torah, the bad news is that we'll have to sift through the verses, and wonder whether they're part of the story of the Israelites, or of the Hebrews. This will be easy in some cases — impossible in others. The good news is that a clearer picture of both groups will emerge. First, we can eliminate the confusion of rationalizing details that just don't belong. Second, the two chronologies actually overlap, meaning that they can inform each other, doubling the number & specificity of inferences that can be drawn. That analysis begins in the article on Moses, Isaac, & Jacob. But first, the next three articles further explore the historicity of the Abrahamic lineage, all of the way back to the beginning.

1. Albright, W. F. (1957): From the Stone Age to Christianity: Monotheism and the Historical Process. Johns Hopkins University Press ⇧

2. Genesis 12:6-7 (J) ⇧ ⇧

3. Exodus 6:8 (P) ⇧

4. Bryce, T. R. (2012): The World of The Neo-Hittite Kingdoms: A Political and Military History. Oxford University Press ⇧

5. Genesis 20:12 (E) ⇧ ⇧

6. Genesis 17:5 (P) ⇧ ⇧

7. Genesis 17:15 (P) ⇧

8. Chandler, T. (1976): Godly Kings and Early Ethics. Exposition Press ⇧ ⇧ ⇧ ⇧

9. Genesis 11:31 (P) ⇧

10. Olmstead, A. (1922): The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. ⇧

11. Genesis 12:10-20 (J) ⇧

12. Genesis 20:1-2 (E) ⇧ ⇧

13. Genesis 26:7 (J) ⇧

14. Benamozegh, E.; Luria, M. (1995): Israel and Humanity. Paulist Press ⇧

15. Moran, W. L. (2000): The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press ⇧ ⇧

16. Genesis 14:14 (J) ⇧

17. Gordon, C. (1954): The Journal of Near Eastern Studies. ⇧

18. Genesis 12:20 (J) ⇧

19. Genesis 12:17 (J) ⇧

20. Kozloff, A. (2006): Bubonic Plague in the Reign of Amenhotep III? KMT, 17 (3): 36-46 ⇧

21. Diodorus (49 bce): Bibliotheca historica. ⇧

22. Genesis 20:7 (E) ⇧

23. Dussaud, R. (1934): Nouvelles archéologiques. Syria, 15 (2): 214-216 ⇧

24. Genesis 15:18-21 (J) ⇧

25. Genesis 17:10 (P) ⇧

26. Wilkinson, J. G. (1854): The Ancient Egyptians. Bonanza Books/Crown ⇧

27. Teeter, E. (2003): Ancient Egypt: Treasures from the Collection of the Oriental Institute. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago ⇧

28. Genesis 18:10 (J) ⇧

29. Genesis 21:1-2 (J,P) ⇧

30. Genesis 21:12 (E) ⇧

31. Genesis 16 (Sarai and Hagar) ⇧

32. Genesis 21:10 (E) ⇧

33. Genesis 15:4 (J) ⇧

34. Genesis 22 (The Sacrifice of Isaac) ⇧

35. Genesis 18:1 (J) ⇧

36. Genesis 17:17 (P) ⇧

37. Matthew 1:1-6 ⇧

38. Silberman, N. A.; Finkelstein, I. (2002): The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Touchstone ⇧ ⇧

39. Genesis 17:21 (P) ⇧

40. Genesis 26:8-16 (J) ⇧

41. Genesis 16:3 (P) ⇧

42. Eusebius (325): Chronicle. ⇧

43. Genesis 23:1-7 (P) ⇧

44. Genesis 14:18 (J) ⇧

45. Joshua 10:1-5 (DH) ⇧

46. Judges 1:4-6 (DH) ⇧

47. Hamzah (960): The Annals of Hamzah Al-Isfahani. K. R. Cama Oriental Institute ⇧

48. Petrie, F. (ed.) (1895): Egyptian Tales, Translated from the Papyri, Second Series, 18th to 19th dynasty, Anpu and Bata. F. A. Stokes ⇧

49. Genesis 24:6 (J) ⇧

50. Genesis 47:11 (J) ⇧

51. Breasted, J. H. (1905): A history of Egypt from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. New York: C. Scribner's Sons ⇧

52. Genesis 46 (Joseph Brings His Family to Egypt) ⇧

53. Genesis 47:28 (P) ⇧

54. Genesis 41:39-40 (E) ⇧

55. Genesis 41:46 (P,E) ⇧

56. Genesis 47:27 (J,P) ⇧

57. Exodus 2:23 (J,P) ⇧

58. Putnam, J. (1990): Egyptology: an Introduction to the History, Art, and Culture of Ancient Egypt. ⇧

59. Exodus 1:7 (P) ⇧

60. Exodus 1:6-10 (J,P) ⇧

61. Kitchen, K. A. (2006): On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ⇧

62. Friedman, R. E. (1987): Who Wrote the Bible? Simon & Schuster ⇧

Russell, C. (2013): Gilukhipa (Khirgipa).