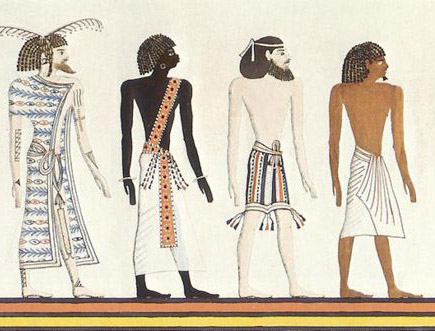

© Charles ChandlerTo find the historical roots of the Torah, we should begin with archaeology. Then we can identify which aspects of the literature line up with the physical evidence.The earliest Hebrew settlements have been dated to the beginning of the .1:35 The settlements were what we would call small towns — home to a couple hundred or a couple thousand people apiece — amounting to less than 50,000 inhabitants in all of Canaan. The only indication that they were Hebrew is simply that no pig bones have been found in the trash heaps — in all other respects, the sites are indistinguishable from Canaanite towns.2:108,3:54,4:19-24 Nevertheless, not eating pork is a distinctive custom that persists to this day, so something happened during this period to affect a lasting cultural change.The absence of any other clearly identifying artifacts is not terribly surprising, since Judaism forbids idolatry.5 In the words of Tacitus,6:35,7:5The Egyptians worship many animals and images of monstrous form; the Jews have purely mental conceptions of Deity, as one in essence. They call those profane who make representations of God in human shape out of perishable materials. They believe that Being to be supreme and eternal, neither capable of representation, nor of decay. They therefore do not allow any images to stand in their cities, much less in their temples.So there simply aren't going to be any religious trinkets to identify Hebrew settlements, and just because archaeology only notes the absence of pig bones doesn't mean that the inhabitants were not already practicing an early form of Judaism. (The Star of David didn't come into use until the 1st Temple Period, and the menorah, though mentioned in the Torah, isn't attested elsewhere before the 2nd Temple Period.) We should also note that in its infancy, Judaism might not have had such strict rules against Canaanite idolatry, perhaps not having settled on how HaShem should be characterized. In other words, they might have been both pagan and Jewish, just as one day there would be a group of Jews who were also Christians, before they locked down on beliefs that just couldn't be reconciled with Judaism. So in the , they might have already sworn to hold no other god before HaShem, but that didn't mean that they had to toss their lesser gods, and while Judaism didn't have any idolatry of its own, they had yet to decide that all idolatry was profane.Now if we look at the contemporary literature, we see other Hebrew customs appearing for the first time during this period. For example, in Figure 1, notice the knotted fringes in the garment worn by the Canaanite in the , and that they are in clumps (left, right, front, & back, making 4 total), as prescribed in the Torah.8,9

1 (E) Now Moses was keeping the flock of his father-in-law, Jethro, the priest of Midian, and he led his flock to the west side of the wilderness and came to Horeb, the mountain of God. 2 (J) And the angel of the Lord appeared to him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush. He looked, and behold, the bush was burning, yet it was not consumed. 3 (J) And Moses said, "I will turn aside to see this great sight, why the bush is not burned."

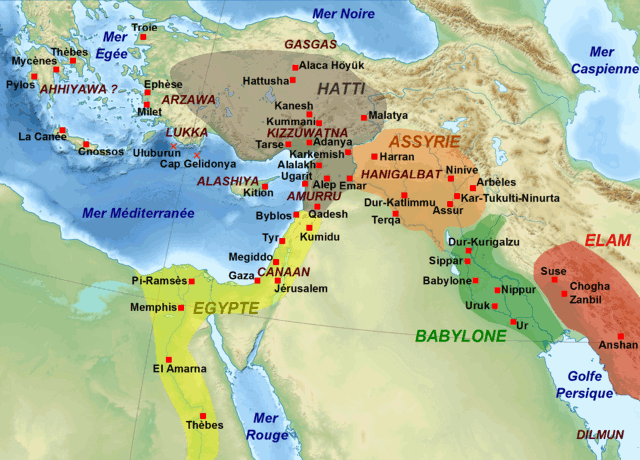

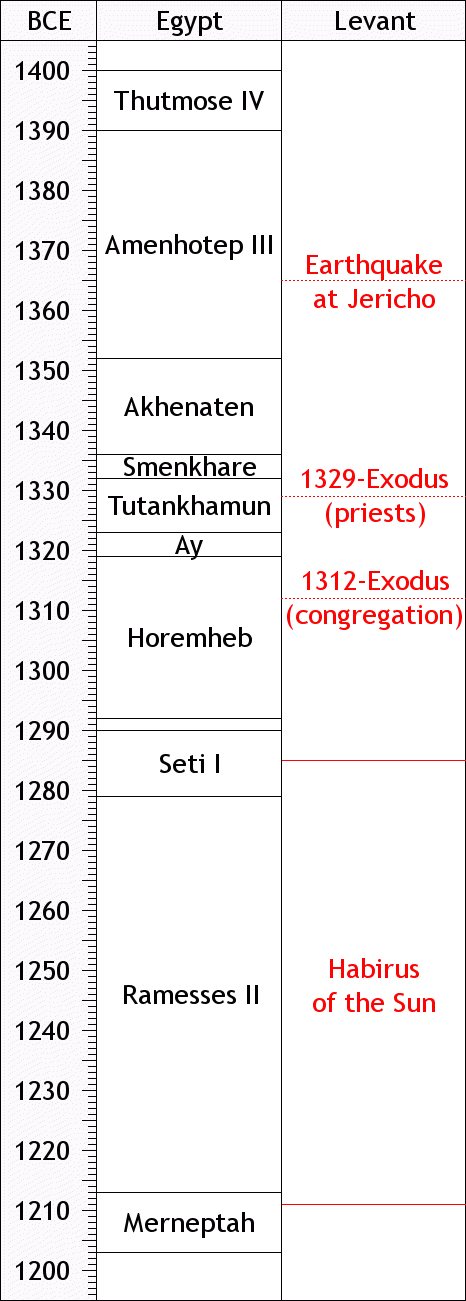

Midian was east of the Sinai Peninsula, while Mount Horeb is thought by many to be at the southern tip of the Sinai, and by some to be in Sudan near the Red Sea coast. Either way, if the shepherd had ventured that far from Midian, the sheep probably would have complained (especially about having to do all of that swimming, which they don't enjoy). The mismatched geography might be the author's hint that we are to interpret the passage loosely. One possible reading is that Horeb is short for Horemheb,11:28 and that the "mountain of God" was the pharaoh, who the Egyptians considered to be a living god. The identification of Horeb as a person instead of a place would make it easier to understand why it is so easy to place Mount Sinai on the map (i.e., in the middle of the Desert of Sin, a well-known geographical region), but so difficult to place Mount Horeb, which is not mentioned outside of the Tanakh, and which various scholars have placed all over the Middle East on the basis of the context in which it's mentioned — Mount Sinai is a mountain that stays in pretty much the same place, while Horemheb was a person who could have met with Moses in any number of places.45,46,47,48,49,50,51Another loose correlation between the Torah and secular history comes from the mention of slaves being put to the task of building structures out of mud-bricks just before the Exodus.52 These would have been dwellings for the people themselves, since public buildings were all built from stone. Ordinarily, such dwellings were built by the people on their own time, so why did the pharaoh commission mud-brick construction on a scale worthy of mention in the Torah? The largest public housing project in ancient Egypt was the rapid construction of Amarna, which became home to roughly 50,000 people after just 2 years ().53 So the oppression of Moses' people, leading directly to the Exodus shortly thereafter, would have been at Amarna.Some scholars dismiss the mention of slaves building mud-brick houses, since slavery wasn't common in Egypt. That might be true, but recent archaeological studies have revealed hardships suffered by the workers at Amarna that can only be evidence of slavery.54:3 So if the uprising described in the Torah is going to line up with secular history, it's going to be in the at Amarna, and it didn't occur in spite of slavery not being common in Egypt — rather, it occurred because of the uncommon oppression at Amarna.Tacitus wrote early in the (based on Lysimachus) that the Exodus began in the reign of Bakenranef,7:5 who all authorities agree came much later. But the story mentions Moses, who led people out of Egypt and into a new country, where they expelled all of the inhabitants, and built a temple. So it's the right story. Interestingly, Tacitus also mentions the outbreak of a contagious disease, which he calls leprosy, but which at the time simply meant "any contagious skin disease." We now know from archaeology that there was a pandemic during the reign of Akhenaten (), father of Tutankhamun.55 And of course the Torah describes plagues just before the Exodus, the 6th of which was a skin disease (perhaps bubonic plague).Lastly (for now), one of the tribes on the Exodus was Asher,56 which settled in Galilee,57 and which is confirmed by an inscription in Seti I's time.58:236-238More evidence will be examined in the next article, but suffice it to say for now that there is easily enough to support the working hypothesis that the Exodus began in the late , consistent with the noticeable appearance of Hebrew settlements in Canaan early in the . So let's begin a time-line (at right), calibrated by the well-known reigns of the pharaohs (using the Low Chronology), and to which we can add the events in Canaan as we examine them. The earthquake that opened the door for Joshua is shown at . Amarna was abandoned in . If the priests were exiled, it might have provided the date used in 1 Kings 6:1 and by Manetho. Horemheb's abolition of Atenism in would have exiled a lot more people, which might be the source of the date quoted in the Seder. (To clearly identify specific waves of exiles, the year is attached, such as the 1329-Exodus and the 1312-Exodus.) The "Habirus of the Sun," as Hattusili III called them, were the Hebrews known to archaeology as having gotten established in the , and who were the ancestors of the modern Jews.Before we continue, we have to acknowledge the evidence that we don't have. The Torah says that 600,000 men left Egypt.59,60 Adding women and children, we would then estimate the total at something like 2 million. There were only 3 million people in all of Egypt at the time.61 This begs the question of why a religious dispute would result in the exile of the majority of the people, leaving the minority behind, instead of the other way around, and suggests that the number was greatly exaggerated. So how many people actually left?There are several ways of constraining the estimate, and all of them require very low numbers.

- The Torah itself states that Moses' followers were the smallest of nations,62 and so few in numbers that if they were the only ones in Canaan, the land would become desolate and overrun by wild animals.63 Elsewhere, it more specifically states that they numbered in the thousands, not tens of thousands or more, or leaders would have been appointed.64,65,66 Just a little later, the people are numbered in the thousands.67

- There is a noticeable absence of archaeological evidence of a mass migration in the Sinai Peninsula. If any sizable number of people left Egypt, we would expect the trail from Egypt to Canaan to be littered with the proof. Yet the finds are not more than what one would expect from the nomadic tribes known to have been there.

- There is no new Egyptian influence in Canaan on construction techniques, pottery, tools, etc.

- A mass migration invariably brings the language of its people to a new land, and the number of words that they add to a local language is roughly proportional to the percentage of the population that moved in. Yet the language of the Canaanites was already established before the Exodus, and changed little because of it.

- The small Bronze Age villages in the Levant couldn't have supported any large group of sojourners. Even in modern times, if thousands of tourists were to descend on a small town in the Middle East that was home to just a couple hundred people, not all of the tourists would get fed. Then word would travel faster than the tourists, and on arrival at the next town, everything would already be gone, including people, possessions, and most importantly, food needed by the locals for their own survival. The tourists surviving such an ordeal would probably want their money back from the travel agency. Likewise, any large group of people in ancient Egypt considering the prospects of a journey across the Sinai would have looked carefully at the total number of people involved, and would not have participated if the group was larger than the desert could support.

This can only mean that if the "Exodus" was an historical event, only a very small group of Egyptians could have been involved.68 For such a small group to have such a profound impact on the culture in the Levant, they had to have been very influential people. We also know that the impact was not on Canaanite construction, pottery, or language, but on religious practices. Hence they were a small group of evangelists, not a large group of colonists, and they left their mark on Hebrew ideology, without leaving much in the way of artifacts for modern archaeologists to dig up. The evidence of a faith centered on an abstract conception of deity is somewhat more subtle. But the Egyptian influence is unmistakable if we look in the right places for it. For example, a number of orthodox Jewish traditions came from Egypt, such as circumcision (brit milah),69,70:34 fringed linen (talit), segregating linen from wool in a garment (shaatnez), and marking a door-post to show membership in a cult (mezzuzeh).71 The people living in Canaan remained distinctly non-Egyptian in all other respects,72:546 except when it came to their most sacred religious practices. This is not evidence of two cultures simply brushing up against each other, where a few of the customs rubbed off. Historically speaking, cultural intermingling quickly alters construction, pottery, and language, but far more slowly alters the most sacred religious practices. This can only be evidence of a small but very influential group of Egyptian evangelists.Who were the evangelists? That question is answered in the next article. But to conclude this article, it cannot be understated that the Exodus wasn't a major demographic shift — it involved a couple thousand Egyptians at most, and to make it across the desert, they had to split up into groups of just a couple dozen people apiece, or they would have starved.73 Still, all of the evidence points to the evangelists leaving Egypt late in the , and the new Hebrew nation thriving in the Judaean Mountains in the .

1. McNutt, P. M. (1999): Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press ⇧ ⇧

2. Dever, W. G. (2003): Who Were the Early Israelites, and Where Did They Come From? Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing ⇧

3. Gnuse, R. K. (1997): No other gods: emergent monotheism in Israel. Sheffield Academic Press ⇧

4. Miller, M. S. (2002): The early history of God: Yahweh and the other deities in ancient Israel. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company ⇧

5. Exodus 20:4 (P) ⇧

6. Strabo (23): Geographica. ⇧

7. Tacitus, P. C. (109): The Histories. ⇧ ⇧ ⇧

8. Numbers 15:38 (P) ⇧

9. Deuteronomy 22:12 (D1) ⇧

10. Schaeffer, C. (1956): Stratigraphie comparée et chronologie de l'Asie occidentale. ⇧ ⇧

11. Chandler, T. (1976): Godly Kings and Early Ethics. Exposition Press ⇧ ⇧ ⇧ ⇧

12. Genesis 1:3 (P) ⇧

13. Numbers 6:24-26 (P) ⇧

14. Deuteronomy 33:2 (D2) ⇧

15. Schmidt, J. D. (1973): Ramesses II. A Chronological Structure for his Reign. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Near Eastern Studies ⇧

16. Josephus, F. (105): Against Apion. ⇧

17. Redmount, C. A. (1999): Bitter Lives: Israel in and out of Egypt. Pgs 79-121 in "The Oxford History of the Biblical World." Oxford University Press ⇧

18. Green, A. R. (1983): Social Stratification and Cultural Continuity in Alalakh. Pgs 181-204 in "The Quest for the Kingdom of God: Studies in Honor of George E. Mendenhall." ⇧

19. Olmstead, A. T. (1931): History of Palestine and Syria to the Macedonian Conquest. Baker Book House ⇧

20. Joshua 6:20 (DH) ⇧

21. Garstang, J.; Garstang, J. B. (1940): The story of Jericho. London: Hodder & Stoughton ⇧

22. Migowski, C. et al. (2004): Recurrence pattern of Holocene earthquakes along the Dead Sea transform revealed by varve-counting and radiocarbon dating of lacustrine sediments. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 222 (1): 301-314 ⇧

23. Judges 11:26 (DH) ⇧

24. Kenyon, K. M. (1957): Digging up Jericho: The results of the Jericho excavations, 1952-1956. Praeger/Ernest Benn ⇧

25. Joshua 13:1-7 (DH) ⇧

26. Moran, W. L. (2000): The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press ⇧

27. Braber, M. D.; Wesselius, J. (2008): The Unity of Joshua 1-8, its Relation to the Story of King Keret, and the Literary Background to the Exodus and Conquest Stories. Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament, 22 (2): 253-274 ⇧

28. Bruins, H. J.; van der Plicht, J. (2006): Tell Es-Sultan (Jericho): Radiocarbon Results of Short-Lived Cereal and Multiyear Charcoal Samples From the End of the Middle Bronze Age. Radiocarbon, 37 (2): 213-220 ⇧

29. Joshua 11:10-11 (DH) ⇧

30. Petrovich, D. (2017): The Dating of Hazor's Destruction in Joshua 11 via Biblical, Archaeological, & Epigraphic Evidence. ⇧

31. Joshua 15:9 (DH) ⇧

32. Joshua 18:15 (DH) ⇧

33. Rendsburg, G. A. (1981): Merneptah in Canaan. Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities, 11: 171-172 ⇧

34. Hoffmeier, J. K. (2007): What is the biblical date for the Exodus? A response to Bryant Wood. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 50 (2): 225-247 ⇧ ⇧

35. Barton, G. A. (1916): Archæology and the Bible. American Sunday School Union ⇧

36. Breasted, J. H. (1905): A history of Egypt from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. New York: C. Scribner's Sons ⇧ ⇧

37. Friedman, R. E. (1987): Who Wrote the Bible? Simon & Schuster ⇧

38. Albright, W. F. (1957): From the Stone Age to Christianity: Monotheism and the Historical Process. Johns Hopkins University Press ⇧

39. Coopersmith, N. (ed.) (2014): Accuracy of Torah Text. aish.com ⇧

40. Charles, R. H. (ed.) (1917): Book of Jubilees. ⇧

41. Moore, M. B.; Kelle, B. E. (2011): Biblical History and Israel's Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Eerdmans Publishing Company ⇧

42. Thompson, T. L. (2000): The Mythic Past: Biblical Archaeology And The Myth Of Israel. ⇧

43. Manetho (250 bce): History of Egypt — Book II. ⇧

44. Greenberg, G. (1999): Manetho's Eighteenth Dynasty: Putting the Pieces Back Together. Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt ⇧

45. Exodus 17:6 (E) ⇧

46. Exodus 33:6 (E) ⇧

47. Deuteronomy 29:1 (D1) ⇧

48. Psalm 106:19 ⇧

49. 1 Kings 8:9 (DH) ⇧

50. 2 Chronicles 5:10 ⇧

51. Malachi 4:4 ⇧

52. Exodus 5:6-9 (E) ⇧

53. Rosenberg, S. G. (2013): The Exodus Enigma. Jerusalem Post ⇧

54. Benderitter, T. (2014): Akhenaten and the Religion of the Aten. ⇧

55. Panagiotakopulu, E. (2004): Pharaonic Egypt and the origins of plague. Journal of Biogeography, 31 (2): 269-275 ⇧

56. Numbers 1:13 (P) ⇧

57. Judges 1:31-32 (DH) ⇧

58. Müller, W. M. (1893): Asien und Europa nach altägyptischen Denkmälern. Leipzig: Engelmann ⇧

59. Exodus 12:37 (S,E) ⇧

60. Numbers 1:44-46 (P) ⇧

61. Chandler, T. (1987): Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census. St. David's University Press ⇧

62. Deuteronomy 7:7 (D1) ⇧

63. Exodus 23:29-30 (E) ⇧

64. Exodus 18:21 (E) ⇧

65. Exodus 18:25 (E) ⇧

66. Deuteronomy 1:15 (D1) ⇧

67. Deuteronomy 5:8-10 (D1) ⇧

68. Faust, A. (2015): The Emergence of Iron Age Israel: On Origins and Habitus. Pgs 467-482 in "Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective: Text, Archeology, Culture and Geoscience." Springer ⇧

69. Wilkinson, J. G. (1854): The Ancient Egyptians. Bonanza Books/Crown ⇧

70. Teeter, E. (2003): Ancient Egypt: Treasures from the Collection of the Oriental Institute. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago ⇧

71. Exodus 12:7 (P) ⇧

72. Dever, W. (1992): Israel, History of (Archaeology and the "Conquest"). Pgs 545-558 in "The Anchor Bible Dictionary." Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., Vol. 3 ⇧

73. Exodus 17:1 (S) ⇧