© Charles ChandlerThe Torah lays the foundation for Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, whose followers amount to nearly half of the world's population, making this one of the most influential documents ever written. It's also one of the most enigmatic. The grammar & vocabulary have been dated to the 1st Temple Period, while the events described therein would have occurred earlier. But the historical passages contradict each other, and are difficult to reconcile with secular records. As a consequence, some scholars have concluded that the actual events might never have happened, and even if they did, the stories we inherit were cherry-picked & slanted to suit the situation in a much later time, thereby destroying all traces of historicity.1:78,2:78,3,4:2-3So it's all fiction, or at least as good as fiction for all we know. But novelists are pretty good about writing stories that don't contradict themselves, for the sake of credibility. Successive generations are also pretty good about reworking fiction, there being no reason to remain true to something that was fabricated in the first place. Such stories accumulate the artistry of poets & minstrels, eventually sporting all manner of literary device, including rhyme, cadence, and sometimes even musical accompaniment. Examples of this can be found in every culture, from the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, to the Greek Iliad & Odyssey, to the English legends of Beowulf & Sir Gawain. The Torah just doesn't fit that pattern. Clearly, the Jewish scribes were not given such poetic license, and were rather expected to leave the stories as close to the originals as possible.5 The massive effort of compiling the Torah was motivated entirely by the conviction that it would preserve real testimony, which of course isn't always poetic, and which sometimes contradicts itself, but which nevertheless has to be transcribed as given. So the original scribes thought that they were preserving authentic information, and with such determination that it became a tradition that persists to this day.There is no question that the testimony contains inconsistencies. When did those enter the literature? Some of them might have already been set when the stories were first committed to writing, if there were differences of opinion even in the first-hand accounts, which of course happens all of the time. Other discrepancies might have been introduced in a much later period, when scribes were trying to make sense of the reports in their own terms, and felt compelled to make changes, thinking that they were fixing problems. That, of course, happens all of the time too. But it isn't so likely that the Torah began as pure fiction. The historical passages that have already been verified by archaeology prove that the scribes had access to historical documents, and it would have been simply easier for them to work with the existing literature — that way, all of the writing was already done, and it had already been accepted by the community, so that's what they would have done. The significance is that despite later redaction, the literature might still be bearing first-hand historical details. Granted we don't know this in advance — any particular verse in question might have been historically accurate when the testimony was first recorded, but it might have been altered after the fact into something that wasn't true. Or it might have been a misrepresentation from the start, because somebody had a motive to lie. Still, we shan't assume that either is the case — we have to look at what the literature says, and then compare it to extra-biblical sources, to see if there are parallels. The point here is just that the historical details might be authentic, if we can see past the redaction. And that, of course, requires that we understand the redaction.

Table 1. Wellhausen's Chronology

name date region Judah Israel Jerusalem Babylonia By scrutinizing the content and style of each verse, scholars in the (starting with Julius Wellhausen) identified four different bodies of literature that got woven together into the Torah that we inherit.6 Clearly there was a common heritage, but in different regions, and during different periods, differences appeared in the way the stories were told. (See Table 1.) The oldest identifiable literary source was popular in the southern province of Judah, and is called Jahwist, because it used YHWH as the name of God (and since Wellhausen was German, he used "J" for the "Y" in Yahweh). The grammar & vocabulary have been dated to , early in the 1st Temple Period. In the northern province of Israel, a different version was in circulation, called Elohist because it used Elohim as God's name. The language in that source has been dated to . The fusion of these two sources began in , when the priests in Israel migrated to Judah to get away from the advancing Assyrians. More material was added, along with more redaction, during the reign of King Josiah (), in what is now called the Deuteronomic Reform. The Priestly source materialized when the Jewish elite were in captivity in , courtesy of King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. After liberating them, Cyrus II of Persia called on the Jewish priests to set up a theocracy in Judah, inaugurating the 2nd Temple Period. This is when the Torah solidified into its present form (along with the subsequent books of the Tanakh, through 2 Kings). There are ongoing debates concerning which specific passages can be attributed to which sources, and in which periods, so we can look to future scholarship for further clarifications of the circumstances in which the Torah took shape.7 But there is little doubt that Wellhausen was fundamentally correct in his assessment that the Torah contains linguistic and ideological differences, which can be traced to different regions and periods of time.Why didn't the people doing each subsequent revision smooth out the inconsistencies, such that the whole thing would read like it was written by one hand? The most plausible answer is that they didn't want to disenfranchise any of the stakeholders. If the redactors had totally reworked the Torah, they would have put a lot of effort into it, and then they would have lost the support of everybody. But preserving as much of the original material as possible, even if it left contradictions, meant that all of the stakeholders could still point to pieces that were distinctly theirs, and thus have a reason to buy into the redaction. Put another way, ancient consensus building probably worked pretty much the same as it does today, and people actually don't have such a huge problem coming to an agreement on a framework that contains dichotomies, as long as they got a few of their pieces into it — then they will say that at least the consensus has some good in it, and it's unfortunate that stupid people had their say, but time will bear out the good parts, and that will validate the smart people — and this is what everybody is thinking — while nobody is caring that the whole thing put together is a mess. So the redactors had to do as little editing as possible, in the interest of not alienating anyone familiar with the original sources.Recent scholarship has tended to assign later dates to the original sources and/or the redactors who produced the final version, if any aspect of it could not have come earlier. This is a bit specious — a thing cannot be properly dated just by the newest aspect of it, nor the oldest for that matter. Unless there is strong reason to believe that modifications absolutely were not allowed, the old aspects are old, and the newer aspects are evidence of revisions. For example, the story of Abraham mentions camels...Genesis 12:1616 (J) And for her sake he dealt well with Abram; and he had sheep, oxen, male donkeys, male servants, female servants, female donkeys, and camels.

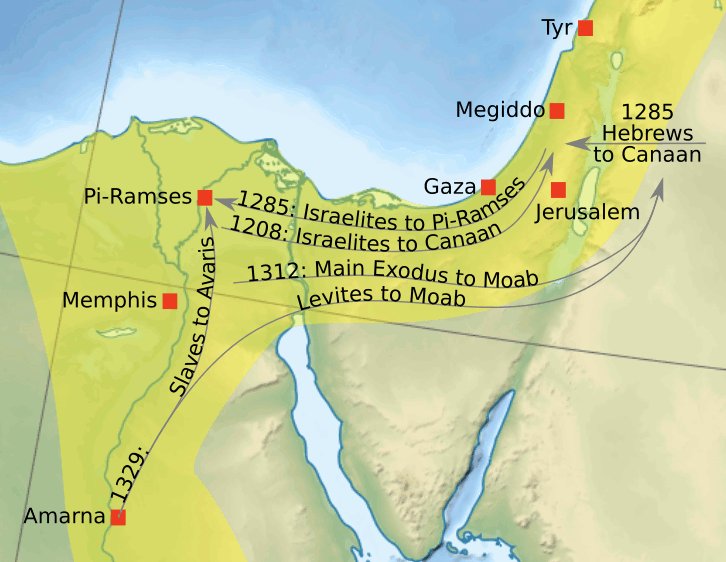

Camels don't seem to have been domesticated in the Levant before ,8 suggesting to some that the entire story of Abraham had to have been composed from scratch sometime after that.9 But the words "and camels" could have been added to the end of the sentence anytime before the final canonization of the Torah, perhaps as late as . So the story of Abraham could have been hundreds of years old by , when a 1st Temple scribe added camels to the property list just so the congregation wouldn't get stuck on why an affluent tent dweller like Abraham didn't have any camels. In no sense would adding another item to a list of assets invalidate the rest of the list, much less everything said about that person elsewhere.Some have even gone so far as to say that if any aspect of the Torah was written at a later date, the entire thing was spun, whole-cloth, at that later date. This is quite absurd — nobody would bother writing such a thing, because nobody else would bother reading it. Inconsistencies in the fusion of ancient and venerable traditions do not preclude a consensus, but without any existing authenticity, a new work full of contradictions is simply flawed. So the inconsistencies are actually evidence that the underlying traditions had to have been much older, and much more deeply rooted than the redactions.Thus the Torah cannot be fully understood as just literature mainly from the 1st Temple Period, with the last redaction coming early in the 2nd Temple Period, as dated by the literary analysis (such as in Table 1). That only tells us about the final rounds of editing. And we're still left with a patchwork of literature. Resolving the discrepancies will require that we look back to the original events that inspired the story in the first place, which were before the 1st Temple.Interestingly, modern archaeology continues to accumulate new evidence, and the analysis of secular and biblical literature continues to yield new insights, making it possible to draw new conclusions. The pivotal event was, of course, the Exodus. But it's becoming clear that there wasn't just one Exodus — there were several. The Levant was the crossroads of the ancient world, and in the period of interest, there were no less than six different migrations that brought new cultural, economic, and political influences into Canaan.10:62,11 (See Table 2 and Figure 1.)

description 1560 Ahmose I exiled the Hyksos to Jerusalem. 1365 "Habirus led by Yashua" sacked Jericho. 1329 Tutankhamun abandoned Amarna, exiling its priests. 1312 Horemheb banished all remaining Atenists from Egypt. 1285 "Habirus of the Sun" moved from Moab into Canaan. 1208 Merneptah abandoned Pi-Ramses, exiling its people.

As an aside, this document adheres to the emerging standard of using a tilde for date ranges. So "" means "from to ." This clearly identifies it as a range and not a subtraction, or some sort of year-month-day combination, making it machine-readable, and laying the foundation for the computerized correlation of literature focused on similar periods in time. It also facilitates the pop-up text that appears when hovering the mouse over a date, showing the Anno Mundi equivalent(s).Also, except as noted otherwise, the English Standard Version (ESV) of the Bible was used, since it is one of the most literal English translations, and without the archaic English preserved in the KJV. And the Babylonian Talmud was used.

1. Miller, J. M.; Hayes, J. H. (1986): A history of ancient Israel and Judah. Philadelphia: Westminster Press ⇧

2. Thompson, T. L. (2000): The Mythic Past: Biblical Archaeology And The Myth Of Israel. ⇧

3. Silberman, N. A.; Finkelstein, I. (2002): The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Touchstone ⇧

4. Whitelam, K. W. (2013): The Invention of Ancient Israel: The Silencing of Palestinian History. Routledge ⇧

5. Coopersmith, N. (ed.) (2014): Accuracy of Torah Text. aish.com ⇧

6. Wellhausen, J. (1878): Prolegomena to the History of Israel. ⇧

7. Friedman, R. E. (1987): Who Wrote the Bible? Simon & Schuster ⇧

8. Sapir-Hen, L.; Ben-Yosef, E. (2013): The Introduction of Domestic Camels to the Southern Levant: Evidence from the Aravah Valley. TEL AVIV, 40: 277-285 ⇧

9. Hasson, N. (2014): Hump stump solved: Camels arrived in region much later than biblical reference. Haaretz ⇧

10. Tubb, J. N.; Chapman, R. L. (1990): Archaeology and the Bible. British Museum Press ⇧

11. Mattfeld, W. R. (2014): Exodus Memories of Southern Sinai (Linking the Archaeological Data to the Biblical Narratives). ⇧