Thunderbolts Forum

CharlesChandlerCall for Criticisms on New Solar Model

A collaboration among some independent investigators (listed below) has yielded a new model of the Sun. And guess what? The Sun is definitely electric! Only 1/3 of the solar power is from nuclear fusion, while the other 2/3 is from arc discharges. And the nuclear fusion is not caused by gravitational pressure in the core. Rather, it's caused by high-energy particle collisions... in arc discharges! So the prime mover is electric currents, without which the Sun would be a dark star, and we wouldn't be here to study it.

While suggestions from a lot of people added value to this project, there were 5 primary collaborators. Please note that not all of them agree on every point. This, of course, is not a problem, as the differences of opinion have always forced a more detailed analysis, and that has always yielded even higher specificity. So don't expect all of them to chime in, and start singing the praises of this new model. Rather, they are its best critics!Still, all of them did a lot of work, and they deserve credit for what they did.

Lloyd Kinder insisted that any analysis of the Sun's density gradient should include Oliver Manuel's work on elemental abundances, which now forms the core of the model. Lloyd then organized and moderated a series of debates, and kept the project going with his gentle but firm insistence on clarity and open-mindedness. Other contributions of his are too numerous to mention. (Lloyd also assists in just about all of the theoretical enterprises going on anywhere within the EU. When does he sleep?)

Dieter Preschel, a colleague of the late Harold Aspden, added the details on compressive ionization, which generates the electrostatic potentials that are getting released by the Sun.

Brant Callahan contributed his extensive knowledge of solar spectroscopy and related issues, including black-body theory, which is the primary form of energy release in the Sun. His theoretical work on the inordinate abundance of iron in CMEs and coronal loops was key in developing an accurate description of solar flares. Such arc discharges are, of course, the products of charge separations, but the resultant CMEs go on to generate the charge separation that drives the solar-heliospheric electric current, which keeps the whole thing going. (Brant also continues to work on his own "wireless" model of solar energy transfer, as well as theoretical work in aetherometry.)

Michael Mozina lent his expertise on the conditions that cause nuclear fusion in the Sun. Also, his knowledge of specific wavelengths in the solar spectrum, and what they tell us about the degrees of ionization of heavier elements, figured significantly in the development of a compete picture of the electric fields, at and above the Sun's surface. (Michael is also championing his own "iron crust" model.)

For my part, I just kept asking questions and sifting through the answers, until all of the pieces started fitting together. (If you try enough combinations, sooner or later, something is going to work.)

Out of all of this, a new model has emerged, which incorporates a wide variety of data, in a self-consistent framework. There's gotta be something to that. What are the chances that a model could address so many issues, to such a high degree of specificity, without contradicting itself, and still be fundamentally incorrect? IMO, it's beyond chance at this point.

So forget about bashing the mainstream model. It will die soon enough, when people stop feeding it. This is the kind of model that you should be bashing!It's just like when Copernicus came up with the heliocentric model of the solar system. That was the time to forget about the problems in Ptolemy's geocentric model, and start looking for the discrepancies in the new system. So Kepler measured the errors in the Copernican orbits, and when he plotted them, he saw that they formed ellipses instead of circles. So he got that piece into place. Galileo saw the need for new laws of motion, and more accurate telescopes. Newton then added gravity and calculus, and voila, the new model became the one to beat. None of these people wasted their time trying to convince the scholastic monks that Ptolemy was wrong. They just got to work on the new system, and made their contributions. Similarly (though on a somewhat smaller scale), there is now a new model of the Sun. Surely it contains plenty of errors, of omission and commission. But it's a fundamentally new way of looking at the Sun that gets all of the big pieces to fit together, and that's enough to make it a player in the solar model game. Now you have two choices: 1) continue to trash the mainstream model, even though it isn't going anywhere, and nobody in the mainstream really seems to care, or 2) find errors in one of the new models, and potentially make a lasting contribution. Keep in mind that Kepler made a name for himself by improving Copernicus' model, not by flaming Ptolemy's.

And make no mistake about this â if you want a piece of this action, just take it. If you want something named after you (like the Harrington granules, or the Erney spicules, or whatever), just pick something in this model that doesn't look right, study the heck out of it, find all of the relevant literature, and write up the new and improved version. Then you'll get credit for that piece. The Sun is a complex thing, and there is a LOT of literature out there. Everybody knows about a different kind of thing. What's your specialty? Somewhere in my write-up, there might be a discussion of it. If so, and if you spot errors, post the fixes. If not, write a new piece from scratch, and show where it fits in. Then again, you might just think that this model is busted and can't be fixed. If so, say so. If you can make a convincing case of it, I'll stop fooling with this model, and I'll look elsewhere for the truth. If I find it, you'll get the credit for setting me straight. If you're working on a totally different model, let me know, and I'll include it in the "Alternatives" section (assuming that you have done a reasonable job of explaining and illustrating your contentions). No matter what, we're going to learn something, and scientific progress will be made by our efforts.

Here's the link to the new model:

http://qdl.scs-inc.us/?top=5237

If you have questions on any of this, just ask, and I'll elaborate on this thread. It's too much material to just post the whole thing here, but the basic idea is that gravity creates compressive ionization, which converts gravitational potential into electrostatic potential. Once the charges have been separated, energy can be released by charge recombination within the Sun. It also enables a solar-heliospheric current that is responsible for 1/2 of the power output. From a distance, it looks very similar to the Juergens model, but it fills in a lot of details, and covers the full gamut of solar science, from heavy elements in the core to high temperatures in the corona, and everything in-between. See the link for more info.

Cheers!

mamusoRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

Take the following with a grain of salt as I'm almost asleep and I've not read the entire website.

The first issue that comes to my mind is the energy source.

Gravitational potential as a source of energy can be used only once, and so stars would be born and death in some way, which should be explained, unless mass is continously falling to the star.

The electric star model which Thornhill uses to talk about solves the issue by placing the source out of the box and setting the question out of scope.

So my first question would be: Does your star die?

CharlesChandlerRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

I agree that a complete solar theory must also include details on the entire stellar life cycle. This aspect of the theory is less mature, but I'll at least air my opinions.

In order to understand how a star might eventually die, we must first understand how it was born. But before we begin, some misconceptions in the standard stellar model need to be eliminated. Gravity is given credit for causing the collapse of dusty plasmas into stars, and thereafter keeping the stars organized. Aside from the fact that gravity is too weak to cause the collapse in the first place, thinking that it will latch onto the matter and compress it into a star is ignorant of Newtonian physics. Any force that could cause the implosion of a dusty plasma would give it the momentum to overshoot the hydrostatic equilibrium. Thus an imploding dust cloud should bounce off of itself, and expand back out to the dimensions of the original cloud. If it doesn't, it is merely because the matter accreted over a period of time, and earlier explosions were muffled by the continuing implosion of more matter, leaving everything stationary, at or close to the hydrostatic equilibrium. But the thermalization of all of the momentum in an imploding dust cloud would produce temperatures (and thus hydrostatic pressures) way out of range for condensed matter. Somehow, all of that hydrostatic pressure has to be converted into another form of potential that is not repulsive, or no star will form.

That "other potential" can only be electrostatic, which can be repulsive or attractive. So somehow, the kinetic energy of the imploding dust cloud gets converted into electrostatic potential, and in a configuration that is not wholly repulsive. How can this happen?

We know from the ideal gas laws that compressing a gas increases the temperature, and thus the hydrostatic pressure, as a direct function of the decrease in volume. We also know that if we compress the gas all of the way down to the density of a liquid, the matter is incompressible past that point. This is because in liquids, the electron shells of neighboring atoms overlap, and further compression will cause the failure of the shells. Since electrons can only exist as free particles or in specific shells, if the atoms are forced too close together, the electrons are expelled. Then we are left with only positive ions, which are repelled by their like charges. Hence it is the electric force that gives liquids their incompressibility. As we continue the compression, and start to squeeze out electrons, the electric force pushes back.

Interestingly, if the pressure continues to increase, the liquid starts getting ionized, and the "temperature" actually starts going down. The enormous electric forces (i.e., repulsion of like charges and attraction of opposite charges) remove all of the degrees of freedom. So you might actually be able to reduce the temperature to absolute zero if you could squeeze out all of the electrons. Where did all of that heat go? It got converted to electrostatic potential. How do you get it back? If you relax the pressure, you enable enough room between the atoms for electron shells. Then the electrons flow back in, and charge recombination regenerates all of the heat that was taken out by the charge separation process.

Now, back to dust clouds. All other factors being the same, an imploding dust cloud that overshoots the hydrostatic equilibrium, and gets compressed all of the way down to a liquid, should just bounce off of itself even more dramatically, because it hit the wall of incompressibility.

But on a stellar scale, we also have to figure the effects of gravity. It is the weakest of the forces present, but it has an important property. Hydrostatic pressure is purely repulsive. The electric force can be either repulsive or attractive. But gravity is purely attractive. This means that if the imploding dust cloud overshoots the hydrostatic equilibrium, before it bounces off of itself, the dense matter will generate a dense gravitational field, with the greatest pressure in the core. So that's where compressive ionization starts. Then things get interesting. Electrons expelled from the core will congregate outside of it, attracted to it by the electric force, but unable to recombine with it, because the pressure won't allow it. So you get a positive core surrounded by a negative double-layer. The negative double-layer can then induce a positive charge in the plasma outside of it, and thus a series of charged double-layers are instantiated, all because of the primary charge separation in the core. Interestingly, these double-layers will be bound tightly together by the electric force. The significance is that this increases the density of the matter, which increases the concentration of the gravitational field, which further compresses the matter, creating even more compressive ionization, which creates even more electrostatic potential. So this constitutes a force feedback loop.

So if the dust cloud overshoots the hydrostatic equilibrium, and creates too great of an excess of hydrostatic pressure, compressive ionization takes hold. Then, the matter clanks together into a star. All of the resting thermal energy of the dust cloud, plus the thermalization of its imploding momentum, get converted into electrostatic potential, and the electric force keeps it all together.

So what is the nature of the heat getting released by a star?

The ancients thought that God had just built Himself so many little campfires. In the 1800s, scientists gained the ability to do spectroscopy, and detected hydrogen in stellar spectra, concluding that the hydrogen was getting burned. But they couldn't find enough oxygen to keep the flame from going out, and they didn't understand how hydrogen could keep burning for at least millions of years, if not longer. In the 1950s, scientists discovered nuclear fusion, and they thought they had it all figured out. The hydrogen wasn't burning â it was getting fused into helium. Ah, but the fusion furnace model still wasn't correct. Then Juergens extended the work of Bruce and Birkeland, in saying that an electric current is providing the heat. He was right, but he didn't establish a charge separation mechanism that could produce a sustained arc discharge.

In the present model, stars have a lot more potential energy than just burnable hydrogen, and more than just fusable hydrogen. Stars actually have all of the thermal energy of a dust cloud that collapsed, which makes the standard model's 15 MK look frigid by comparison. Of course, all of that thermal energy, if it was still thermal, would be impossible in condensed matter. But it isn't thermal â it has mostly been converted to electrostatic potential. The core of a star might actually be at absolute zero, though with enough potential to heat a stellar system for billions of years.

So how does this energy get released?

The solar model has a far more detailed answer to this, but in the general stellar model, it's just mass loss due to stellar winds that relaxes the pressure. This allows charge recombination, converting electrostatic potential back into heat. The heat then helps drive the stellar winds, which perpetuate the mass loss. In rough terms, stars are "boiling away", where the mass loss in the "steam" enables more of the liquid to boil.

So yes, such stars will eventually die. I'm thinking that stars are born as blue giants, and then eventually wither down the main sequence into red dwarfs, and then finally into planets, once there is no longer the pressure for compressive ionization near enough to the surface to drive a stellar wind.

I have over-simplified all of this, for the sake of readability. And it is only representative of the Sun in the roughest of terms. But this is what I'm currently using as a general stellar model.

ElecGeekMomRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

I don't think I will be coming up with actual "criticism" of your theory, but I have some questions that I could use to "poke around" it.

You're the second person I have found who says that planets were formerly stars. When that happens, according to your theory, what makes up the core of the resulting planet?

CharlesChandlerRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

Where I used the term "planet" I could have also just said "dark star," for all of what I actually meant. In other words, I'm not explicitly stating that all planets used to be stars. Some of them might still be in the accretion process, yet to become a star if they can ever get together enough mass. So I'll answer the question as if I had said "dark star" and you were asking about the core constitution.

In the proposed model, hydrogen & helium make up 66% of the Sun's volume, with heavier elements (i.e., iron, nickel, platinum, & osmium) making up the other 34%. That's a lot of heavier elements, considering that the Milky Way is estimated to be 98% hydrogen & helium, and only 2% heavier elements.

There are two possibilities here: 1) the Sun condensed from stuff that just happened to have a lot of heavier elements, and 2) the Sun manufactured the heavier elements, by nuclear fusion.

Let's start with #2. The Sun is no longer massive enough for nuclear fusion in its core, even just to be fusing hydrogen into helium. The fusion that does continue to occur is all inside arc discharges, where relativistic electrons slam into high-pressure plasma. I find it hard to believe that this variety of nuclear fusion produced all of the helium, and all of the heavier elements, in the Sun.

I find it easier to believe that the Sun used to be a much heavier star, like a blue giant, capable of fusing all of the heavier elements in its core. It may have started with mostly hydrogen. Over a period of time, heavier elements were manufactured, which remained in or near the core, because their weight got them to settle to the bottom. While the fusion was still active, there would have been a lot of mixing in the core, but the heavier elements never would have risen to the surface. Meanwhile, mass loss to solar winds reduced the force of gravity. With all of the plasma under a lot less pressure, the black-body radiation is now a lot cooler, and the Sun is a yellow dwarf, but it has a big inventory of heavier elements, left over from its younger days.

If this progression is correct, eventually the Sun will be a brown dwarf, with even more heavier elements, less hydrogen, and producing even less light. When it finally goes out, it will be mostly heavy elements.

Note that this does leave a few tidbits on the table, as concerns the constitution of planets, moons, asteroids, etc. These all have a lot of heavier elements as well. If the Sun used to be all hydrogen, and it manufactured all of its own heavier elements, and if the planets, moons, & asteroids condensed out of the same stuff, they should be mainly hydrogen (which means that they wouldn't have condensed). So maybe the planets etc. came out of the Sun as a consequence of a collision that occurred after it had manufactured a lot of heavier elements. Maybe there was another collision, like between two dark stars, and the debris just happened to get trapped by the Sun's gravitational field. Or maybe the Sun is a 2nd generation star, born of the debris of an earlier star that manufactured the heavier elements, and the planets etc. condensed out of the same debris.

ElecGeekMomRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

Thank you for the quick response.

I have more questions:

1. What part does water play in the life cycle of stars?

2. Do you think a star could ever reverse direction in its life cycle? In other words, if it began as a blue giant and then lost power and ended up as a black dwarf, do you think it might ever re-ignite in visible glow mode? I'm thinking of how the stars and planets travel around, perhaps into, or out of, Birkeland currents. Could a star fall out of a relatively strong Birkeland current for a while, then end up in a strong one again? Would that make it likely to end up in glow mode again? As long as it is in dark mode, could it be more of a gatherer of matter than an expeller of energy/mass/whatever? But once it got back into glow mode, it would expel more than it gathers?

I fail to understand how two stars could collide. If they are the same charge, wouldn't they tend to repel each other?

CharlesChandlerRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

1. If it's an active star, the temperatures are too high for water molecules. There might be plenty of hydrogen & oxygen plasma, but no water.

2. I'm not ruling out the influence of external fields (electric or magnetic), and there are lots of them (solar, heliospheric, spiral arm, galaxy, cluster...). One effect of external magnetic fields is that they tend to orient things that rotate (such as planets around stars, or the accretion disc of a planetary nebula). I personally believe that there is an electric field running through the arms of spiral galaxies, where the planets & stars are negatively charged, and the interstellar plasma is positively charged. I believe that this field gives the arm tensile strength, without which the outer reaches would fly off into the intergalactic medium. But I don't know of any evidence of currents per se. It doesn't mean that they aren't there. It just means that they haven't been detected yet, at least on a scale that could do something dramatic, like light up a star. But it would certainly be possible for an old star to run into a new debris field, and to start accreting a whole bunch of new stuff, lighting up and getting brighter as a result.

3. I "think" that if two stars were going to collide, the inertial forces would dominate the event. If they were of like charge, the repulsion would probably blow some charged material off of each of them, but the main bodies of the stars would continue in for the collision.

Cheers!

LloydRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

Math: Final Touches?

Hi Charles. I'm glad to see more progress on your model. I haven't read all of your new material on your website yet, but it's hard to tell what's new anyway. It would be nice if you had an outline of your model incorporated into your webpages. But maybe it's too soon for that. Maybe you need to put the final touches on your model first, assuming no one spots a major error anywhere, by working out the math for the model.

Accretion?

Glad to hear EGM's and others' questions about the source of the Sun's energy etc. That will need some math to back it up too, eventually. It may be that there was a time when there were no galaxies, so accretion may have occurred initially in the way you've suggested, but there's not much astronomical evidence to go on for that suggestion, is there? The Arp and Thornhill models for accretion seem to me to have a lot of good astronomical evidence. Thornhill, as I understand, modifying Arp's model, considers that AGN's, i.e. Active Galactic Nuclei, act as plasma guns that shoot out quasars and B.L. Lac objects in opposite directions, usually polarly, stripped of many or most electrons, which remain behind for a time, and these quasars and objects scavenge intergalactic space for electrons, which slows them down and increases their mass and they evolve into companion galaxies. While you're waiting for anyone to find holes in your model, maybe you could look for holes in that model of "accretion" of quasars etc, including also for whether AGNs could act as plasma guns. I think Thornhill regards planetary nebulae as similar plasma guns, on a much smaller scale, that shoot out mere stars, instead of quasars, so your view on that would be interesting too.

Invitations

If you haven't already invited folks on the main EU board to check your model for errors, as you did here, I'll see if I get time to do it myself. Thanks a lot for all your hard work, clarity and compliments.

CharlesChandlerRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model Lloyd wrote:OK, I implemented a "Changes" page, which you can use to find all of the pages that have changed, and what changed in them, since the date/time that you select. That should make things a lot easier on everybody (including me).It's hard to tell what's new anyway.

http://qdl.scs-inc.us/?top=9656Lloyd wrote:It's already divided up into 12 sections, each only a couple of printed pages long. But I can work more on the fine-grain structure as time goes on.It would be nice if you had an outline of your model incorporated into your webpages.

Lloyd wrote:I'm thinking about adding an appendix, so I can post more of the maths and code, without overloading the text. The finite element analysis engine that I developed currently can calculate pressures, densities, and temperatures, just given the force of gravity in a star. I'm currently reading up on the physics of supercritical fluids, so that I can add in the appropriate Coulomb forces. I'm doing it with FEA because it's a totally explicit approach that everybody can understand. To do these calcs algebraically would take a fourth order tensor that nobody would understand!Maybe you need to put the final touches on your model first, assuming no one spots a major error anywhere, by working out the math for the model.

Lloyd wrote:I was thinking about that. Perhaps I can locate some stats on the average size of a dust cloud, the likes of which is going to condense into a star. Assume that the temperature is 2.7 K (i.e., the cosmic background radiation). Then apply the ideal gas laws, to get the temperature of the condensate. A dust cloud that is a couple of light years across, when compressed into a star a couple million meters across, is going to produce some pretty outrageous temperatures. And that wouldn't even include the thermalization of the imploding momentum. I guess if I knew the rate at which dust clouds collapse, I could throw that in too. Just the ideal gas laws will prove the point, but it would be nice to be able to show exactly how much temperature there was to start, as this is the amount of heat that ultimately will be released by the star in its lifetime.Glad to hear EGM's and others' questions about the source of the Sun's energy etc. That will need some math to back it up too, eventually.

This number can also be used to double-check my estimates of the electrostatic potentials inside a star, as I'm saying that most of the thermal potential has been converted into electrostatic potential, and that's why the temperature of a star is several thousand kelvins, instead of several gazillions. If I can show that the same electrostatic potentials that answer so many questions about the star itself also account for all of the missing thermal energy from the original accretion, it will paint a much bigger picture.Lloyd wrote:You're right. I think that it's interesting to wonder how the very first aggregates formed, and a complete model has to include a plausible mechanism for this. But there will never be any direct evidence one way or the other.It may be that there was a time when there were no galaxies, so accretion may have occurred initially in the way you've suggested, but there's not much astronomical evidence to go on for that suggestion, is there?

Lloyd wrote:There is plenty of evidence of axial jets, on a wide range of scales, as you say. But is there any evidence of stellar nurseries in the jets?Thornhill, as I understand, modifying Arp's model, considers that AGN's, i.e. Active Galactic Nuclei, act as plasma guns that shoot out quasars and B.L. Lac objects in opposite directions, usually polarly, stripped of many or most electrons, which remain behind for a time, and these quasars and objects scavenge intergalactic space for electrons, which slows them down and increases their mass and they evolve into companion galaxies. While you're waiting for anyone to find holes in your model, maybe you could look for holes in that model of "accretion" of quasars etc, including also for whether AGNs could act as plasma guns. I think Thornhill regards planetary nebulae as similar plasma guns, on a much smaller scale, that shoot out mere stars, instead of quasars, so your view on that would be interesting too.

Anyway, what I found intriguing about such jets is the question of what causes the jets in the first place? These are steady streams of particles, predominantly positive, that stay collimated for extreme distances, until they eventually buckle and disperse, looking somewhat like a high-pressure jet shooting into a low-viscosity fluid (hence, of course, the colloquial name for them). The standard model has some gibberish about the jets relieving the pressure in the accretion disc. Some even say that without the jets, the accretion wouldn't even occur anyway, as the matter needs an outlet, or it would all just pile up in the middle, and the accretion would stop. That's not exactly what I would call mechanistic reasoning.

So I looked at it, and this became one of the reasons for settling on the "natural tokamak" concept for extremely high-energy stars. The basic idea is that the star is spinning so fast that the magnetic fields confine the plasma, and instantiate a nuclear fusion reactor, by the z-pinch effect. The first question that this answers is gamma-ray sources. Everybody else's model of nuclear fusion has it occurring in the cores of heavy stars. But all of the gamma rays from the interior of stars should get absorbed by the overlying plasma. In fact, gamma rays are absorbed by all but the thinnest gas clouds. Yet fusion requires incredible pressures. How do you get incredible pressures, without any surrounding plasma to push in on it? I think that there is actually only one answer to that: magnetic pressure. So if you can get the star rotating fast enough, it can fuse heavier elements, without any overlying plasma to supply the pressure. Then you get gamma rays escaping straight out into space, as magnetic fields don't block photons.

At the same time, the "natural tokamak" is the only sustained energy source with bipolar jets. Obviously, fusion in the core of a star isn't going to produce bipolar jets. The overlying plasma will absorb the momentum of the fusion products, and the high pressures will instantiate turbulence. So you'll get a spurt this way, and then that way, out of a deal like that. It's doubtful that any of the spurts would even break the surface of the star. So bipolar jets aren't caused by core fusion. And if it was just pressure from the accretion disc, the ejecta would radiate in all directions, without being collimated. But a toroidal energy source would produce precisely this pattern. If particles are emitted in all directions, 50% of them are heading toward the interior. These collide with each other, with the result being a collimated jet.

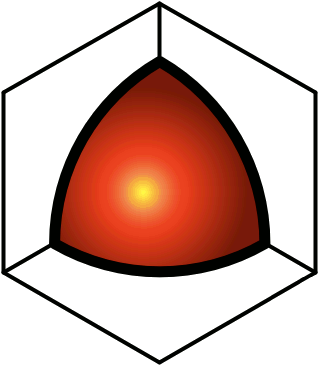

Section of a toroidal explosion

PlasmaticRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

Havent read more than the contents of this thread but wanted to commend the refreshing approach to persuation and communication in the process of discovery! My favorite thinker once pondered if honesty might be a facet of intelligence, the unwillingness to insulate ones views from criticism is,to me', a corrolary to that trait of great thinkers!

GaryNRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

@CharlesAnyway, what I found intriguing about such jets is the question of what causes the jets in the first place? These are steady streams of particles, predominantly positive, that stay collimated for extreme distances, until they eventually buckle and disperse, looking somewhat like a high-pressure jet shooting into a low-viscosity fluid (hence, of course, the colloquial name for them).Can you point me to the research and information about the detection and analysis of the jets, and how they determine an outwards flow? As far as I can determine, just because it looks like a jet doesn't mean it is a jet, and could just as well be a very long thin vortex in a Birkeland current, the Sun being the pinch point, and the flow inwards and not outwards. Ta.

CharlesChandlerRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

The "Butterfly Wings" planetary nebula has been well-studied, as it is fairly near, and fairly bright. The axis of its bipolar jets is nearly perpendicular to our line of sight, so motion along the axis cannot be determined directly by redshift. So these researchers studied light scattered from the nearby dust:

Schwarz, H. E.; Aspin, C.; Corradi, R. L.; Reipurth, B., 2012: M 2-9: moving dust in a fast bipolar outflow. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 319: 267-273Using optical images and spectra of the bipolar nebula M 2-9 we show that, in addition to the well-known bright inner nebula, the object has fast, highly collimated outflows reaching a total extent of 115". These radially opposed and point-symmetric outer lobes are both redshifted, leading us to model the radiation from them in terms of light reflected from moving dust, rather than intrinsic emission. Our polarization images show that the lobes are 60% linearly polarized in a direction perpendicular to the long axis of M 2-9. This high polarization indicates optically thin scattering, and lends weight to our dust scattering model. Use of this model then allows us to determine the distance to M 2-9 directly from the measured proper motions on images taken over a period of more than 16 yrs. The physical and geometrical parameters of the nebula then follow. M 2-9 is at a distance of 650pc, is 0.4pc long, has a luminosity of 550Lsun_, and its outer nebula has a dynamical age of 1200yrs, in round numbers. Using the fact that the central object has been constrained to be of low luminosity but of a sufficiently high temperature to make the observed OIII, we argue that the central object of M 2-9 has to contain a compact, hot source, and is probably a binary.I disagree with their conclusion that the source is a binary, as no one has demonstrated how two stars could get together and produce such a phenomenon. I think that astronomers are fond of binary models simply because they know that a single star could never produce such collimated structures. But I never found the binary model any more convincing, and my ongoing quest for answers eventually turned up the toroidal plasmoid construct.

As always, the interpretation of the data can be challenged, and sometimes, just separating the actual data from the "model data" can be difficult, depending on how the research is written up. But before you lock down on an alternative interpretation, question it. What if we subject our own models to the same critical scrutiny that we apply to everybody else's? "You might be wrong, therefore I might be right" will give you a little bit of wiggle room, but don't dig your heels in and call that a position, because it isn't.

For example, if you say that the flow is inward in a planetary nebula, what is the force that pulls matter in like that? Are you saying that it's an electric current? Do a diagram of the electric fields that would cause such a current, and then explain what would sustain the fields long enough to produce such structures. If you're saying that it's an electric current flowing through the system, then the field is everywhere. Free space has a higher permittivity than the aggregation of plasma and dust in the nebula. So why is the current flowing through the nebula? And what got the current density to be so much greater at the pinch point, such that the magnetic fields would be that much stronger, just right there? If such questions are not answered, then sooner or later, people are going to begin to suspect that it's because they cannot be answered.

The better approach is not to lock down on a position, but rather, to make progress the constant factor. As more information keeps coming in, keep sifting through it, trying to make sense of it, and figuring out what that does to existing notions. That will keep you on the forefront of the advances in knowledge and understanding.

SparkyRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model What are the chances that a model could address so many issues, to such a high degree of specificity, without contradicting itself, and still be fundamentally incorrect?Excellent point!

Have you addressed the "field lines" inexactness issue some where?

Will plasma find a minimal flux density, be confined by it, and follow it?

CharlesChandlerRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

Hey Sparky!Sparky wrote:Which field lines, and what inexactness?Have you addressed the "field lines" inexactness issue some where?

Sparky wrote:Bipolar jets appear to stay collimated by virtue of their magnetic fields.Will plasma find a minimal flux density, be confined by it, and follow it?

First, there isn't any obvious reason for plasma with a net charge to not get dispersed by electrostatic repulsion. This strongly suggests that a force is opposing the repulsion, and the likely candidate would be the magnetic pinch effect.

Second, bipolar jets appear to be parallel to whatever external magnetic field is present. In the case of planetary nebulae, they are lined up with the spiral arm B-field. In the case of galactic jets, they are lined up with the cluster field. If they weren't charged particles generating magnetic fields, they wouldn't be influenced by an external field.

Third, galactic jets eventually get wobbly, and then they break up. Clearly, the organizing principle somehow lost force. If they were high-pressure jets being shot into a viscous fluid, the "beaming" effect in fluid dynamics would act like that. But it's hard to believe how there is that much friction in the intergalactic medium to create this fluid dynamic effect. My thought is that the jet stays organized due to the magnetic field it generates, but even just a little bit of friction over a long period of time will slow down the jet. The significance is that reduced velocities produce reduced magnetic pinch effects. So the jets convert from laminar beams to turbulent dispersions not because they exceeded some sort of galactic Reynolds number, but because they slowed down, and the magnetic fields were no longer strong enough to contain the plasma.

At least that's my take on it, though I'm no an expert on AGNs.

LloydRe: Call for Criticisms on New Solar Model

Quasar Model

Charles, I didn't understand your reply to my question about Thornhill's quasar model. You talked about bipolar jets, I guess from galaxies, but I was talking about quasars rather than jets. I don't know if there's a difference between plasmoids and quasars or between plasmoids and stars, but I think they're all ionized blobs (aren't they?), whereas I think jets are sprays of diffuse matter. I don't know of jets being significantly involved in Thornhill's quasar model.

Cause of Accretion

I think his stellar model is similar. Like AGNs forming plasma guns that shoot out quasars, planetary nebulae form plasma guns that shoot out smaller plasmoids, which are stars, if I understand him correctly. The accretion in both cases then would be a result of plasma gun action. If you say accretion is due to a natural tokamak, would that be very similar to or different from a plasma gun?